a16z's Big Ideas 2026 thesis makes a sharp observation: the AI constraint is shifting. In 2025, the conversation was dominated by compute -- who has enough GPUs, who is building data centres fast enough, who can afford the training runs. In 2026, the binding constraint moves to data.

Not data in the general sense. The internet has been scraped. The public datasets have been exhausted. The next frontier is the data locked inside critical industries -- healthcare, insurance, government, infrastructure -- that remains unstructured, messy, and largely untouched by AI.

This is where the real opportunity lives. And it is where building gets hard.

The data everyone ignores

The AI industry has a preference for clean data. Models are trained on curated datasets. Benchmarks are designed with controlled inputs. Research papers evaluate performance on images that have been carefully selected, formatted, and labelled.

The data that matters in critical industries looks nothing like this.

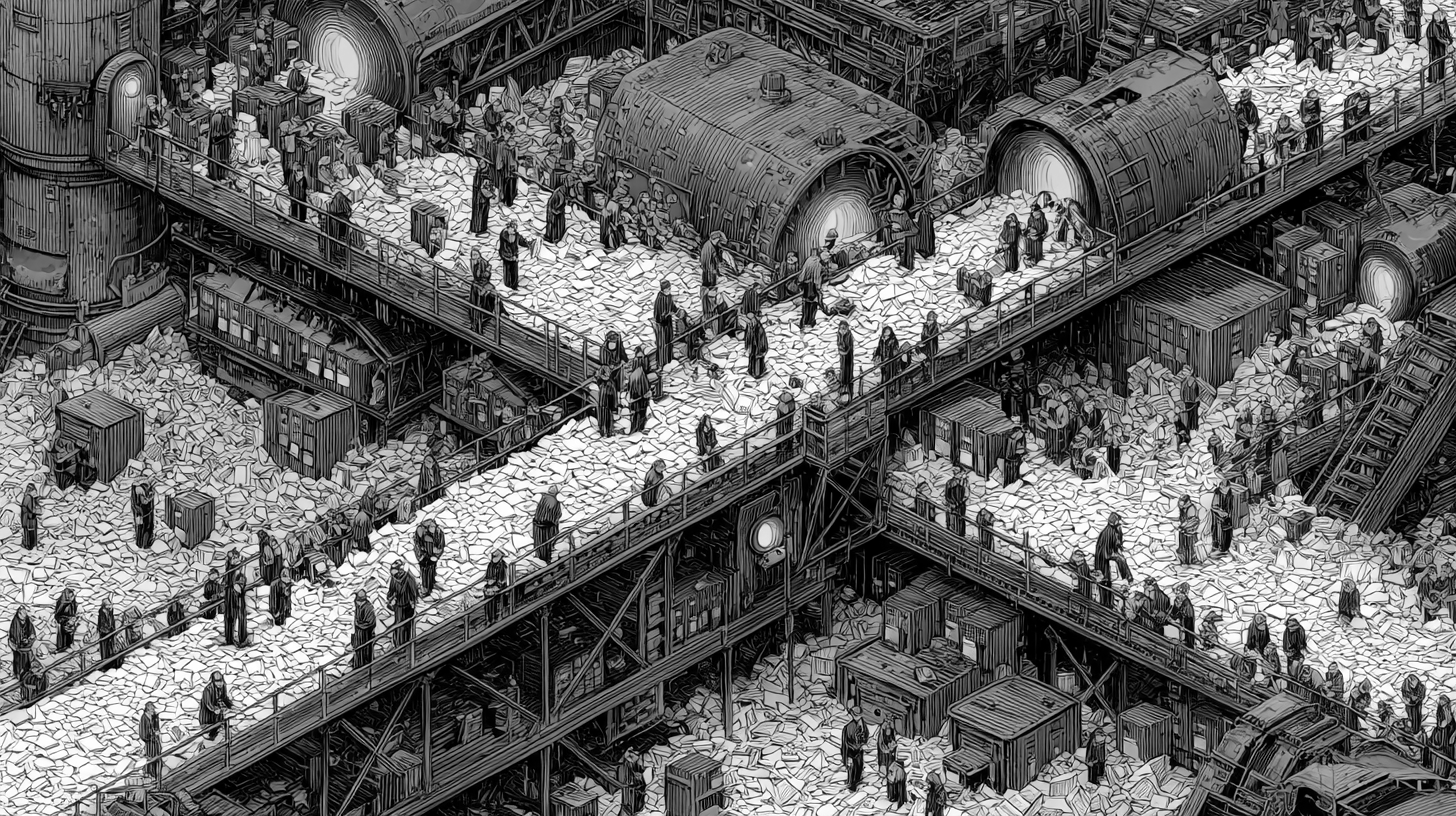

Insurance claims arrive as smartphone photos compressed through WhatsApp, PDFs that have been scanned and re-scanned until the text is barely legible, handwritten notes photographed at an angle, medical records in proprietary formats, repair estimates generated by legacy software that exports to CSV with broken encoding. This is not data that a general-purpose model can handle out of the box. It is data that requires purpose-built systems designed for degraded, inconsistent, multi-format inputs.

Healthcare is the same. Patient records span decades of different EMR systems. Diagnostic images vary wildly by device manufacturer, facility, and protocol. Government agencies operate on forms designed in the 1990s, processed through workflows that predate the internet.

These industries are not data-poor. They are drowning in data. The problem is that none of it is in a form that existing AI systems can reliably process.

Why this is a moat, not a problem

The instinct in AI is to treat messy data as an obstacle. It is actually a competitive advantage -- if you are willing to do the work.

Companies that build models capable of handling real-world data in a specific industry develop something that is extremely hard to replicate: domain-specific data pipelines, preprocessing systems tuned to the exact degradation patterns of that industry, training sets that reflect actual production conditions, and evaluation frameworks that measure what actually matters to the customer.

A horizontal AI company cannot build this. They do not have the data. They do not understand the degradation patterns. They do not know which edge cases matter and which do not. They are optimising for the wrong metric on the wrong distribution.

This is exactly what we discovered building deetech. The deepfake detection models that existed were trained on high-resolution benchmark images. Insurance claims data is compressed, degraded, multi-format, and messy. Building a detector that works on benchmark data is a research project. Building one that works on claims data is a product -- and the data pipeline required to bridge that gap is the moat.

The garbage-in problem nobody talks about

There is a dirty secret in enterprise AI: most deployment failures are not model failures. They are data failures.

The model works fine. The data it receives in production is nothing like the data it was trained on. The preprocessing pipeline was built for the training distribution, not the production distribution. The input validation catches formatting errors but not quality degradation. The monitoring tracks model metrics but not data drift.

In insurance, a single claim can contain a photograph taken on a 2019 Android phone in portrait mode, compressed through three different messaging platforms, saved as a BMP, converted to PDF, printed, scanned back in as a TIFF, and uploaded through a web portal that converts it to JPEG at 60% quality. The model that analyses this image needs to produce a reliable result despite the fact that the original signal has been mangled beyond recognition.

Building for this reality is unglamorous. It means spending more time on data engineering than model architecture. It means your test suite has more edge cases than your competitors have training examples. It means your preprocessing pipeline is more complex than your model.

But it is also why, once you have built it, nobody else can easily catch up. The data pipeline is the product.

Critical industries are the prize

a16z identifies critical industries -- healthcare, insurance, government, energy, infrastructure -- as the data frontier. These are industries where the data is abundant but unusable in its current form, where the regulatory environment creates compliance requirements that general-purpose tools cannot meet, and where the cost of getting it wrong is high enough that reliability matters more than sophistication.

This is also where the commercial opportunity is largest. Insurance processes billions of images annually. Healthcare generates petabytes of diagnostic data. Government agencies handle millions of forms. The TAM is enormous, but only accessible to teams that can handle the data as it actually exists.

The pattern is consistent: the industries with the messiest data have the largest unaddressed markets. The messiness is the barrier to entry. If the data were clean, every horizontal AI company would already be there.

What this means for how we build

At [r]think, this shapes how we evaluate every venture. The question is not "can AI solve this problem in theory?" The question is "can we build a data pipeline that makes AI work on the actual data this industry produces?"

If the answer requires clean, structured inputs that the industry does not generate, the venture will fail at deployment regardless of how good the model is. If the answer requires building a purpose-built data pipeline that handles the specific degradation patterns of that industry, the venture has a moat -- but it requires deep domain work that cannot be shortcut.

deetech exists because we asked this question about insurance claims media and were willing to do the data engineering work that the answer required. The model is important. The data pipeline that makes the model work on real claims is what makes it a product.

a16z is right. The compute constraint is easing. The data constraint is tightening. The builders who win 2026 will be the ones who go deep into messy industries and build the data infrastructure that makes AI actually work.